Developer experience teams have become increasingly common over the past five years. Here’s everything you need to know about how they work.

Despite the growing number of developer experience teams in tech companies, these groups don’t yet share a common framework for how they should be run. This is apparent both in their naming and their varying scopes of work: we see developer productivity teams, engineering effectiveness, and engineering enablement, and we see some groups focus more on tools and others more on people.

Regardless of their names or defined scope, these teams share an underlying principle to improve developer productivity by reducing friction from suboptimal tools and processes. As we’ll explore in this piece, these teams can bring about important improvements to an engineering organization’s productivity.

As more organizations invest in DevEx teams, it’s important to have clarity around how they should work. Through my company, DX, I’m fortunate to have had many conversations with customers and podcast guests around this topic. Here, I’ll share what I’ve learned about how developer experience groups typically define their scope, evolve over time, decide what to focus on, and partner with engineering teams to create change.

Note: this article focuses on internally facing DevEx teams. There are also external-facing DevEx teams that focus on the user experience of products used by developers.

What is a developer experience team?

Ask nearly any developer experience team leader what their charter is, and you’ll hear something like, ‘we make software engineering easier at our company.’ Here are some real-life examples of DevEx team charters at familiar companies:

- Slack: ‘Making the development experience seamless for all engineers’

- Stripe: ‘Make software engineering easier at Stripe’

- Google: ‘Making it fast and easy for developers to deliver great products’

- Snyk: ‘Make Snyk a pleasure to develop within’

- Twitter: ‘Create a seamless and holistic experience for engineers at Twitter’

- Financial Times: ‘Make things as easy as possible for product developers, whether that be by providing tools, clarity, support, or standardization’

- Ibotta: ‘Build happy and high-performing teams by making sure tooling, culture, and processes aren’t getting in the way of engineers’

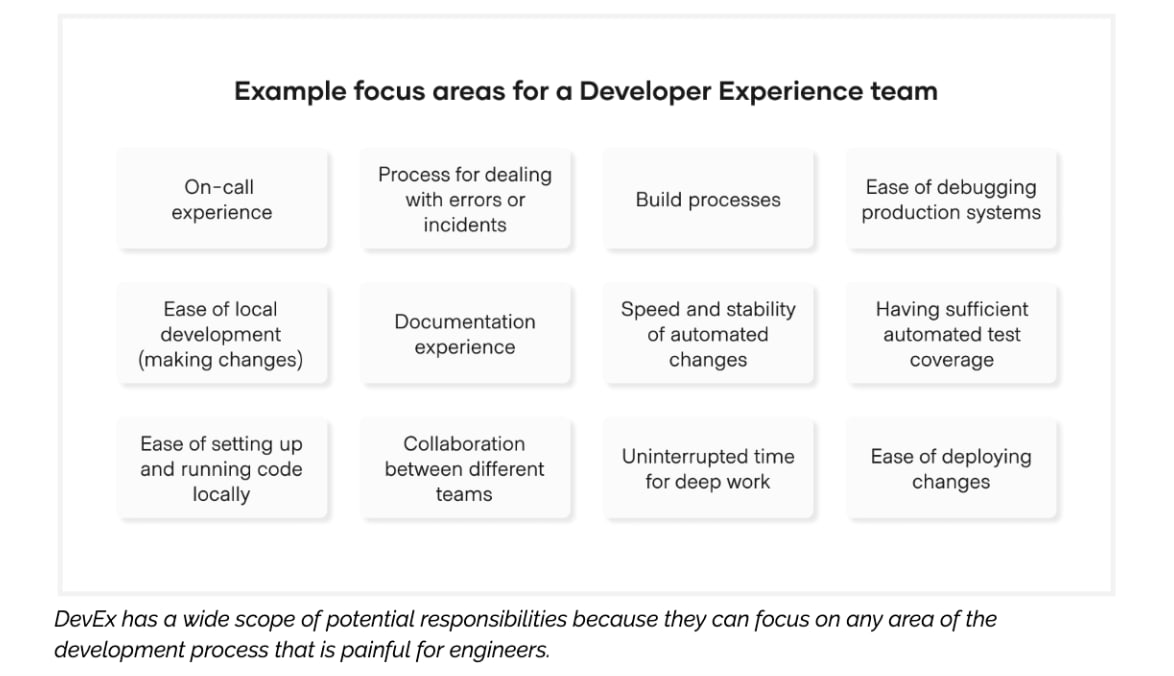

Developer experience teams share a focus of understanding where engineers are struggling, have high cognitive load, or are doing undifferentiated heavy lifting within the development process, and then creating solutions to solve those problems. Typically, teams will prioritize areas that have the biggest impact on productivity for a large number (or mission-critical group) of engineers.

The journey to becoming a developer experience team

Most DX teams follow a similar path as they mature:

Stage 1. An existing team takes on a specific DevEx project. For example, Snyk’s platform group discovered that builds were failing often. Crystal Hirschorn, Head of Platform, said, ‘We broke down the different types of failure states and saw that builds were failing about 70% of the time. We could see that was significant, and a high cost to us… We took that data to the SVP of Engineering to make a case for investing in that problem.’

Typically an existing team within the platform or infrastructure organization will tackle the initial project before a dedicated team is formed.

Stage 2. A dedicated team is formed that sits where the problem exists. Some organizations may form a dedicated group that sits with one engineering team, a product vertical, or a group that matches a specific persona, to solve a problem. The problem may be experienced across the organization, but this group works to solve the problem within one team first. Once a solution has been incubated at the local team level and the value for solving that problem is clear, it may then be scaled more broadly across the organization. (For context, this is how Netflix would test these types of investments.)

At this point, the group may ‘graduate’ to become a centralized team within the platform organization.

Stage 3. A centralized DevEx team is formed. A centralized team may be formed because the initial project deserves more work or needs to be supported, or because other needs arise.

The DevEx team may expand their work into two lanes: their strategic bets (projects that solve issues that are experienced across the organization), and support requests from developers.

Their strategic bets are the primary projects the team decides to focus on that they expect will result in productivity gains for the organization. Support requests may include 1) reported bugs and feedback on the tools the DevEx team has built, or 2) general feedback from developers about their workflow (for example, problems they’re experiencing).

At this stage, the DevEx team risks becoming an ‘everything department’ because many problems that are surfaced are not owned by any other team. As a result, the team may slip into treating their backlog like a roadmap, instead of proactively prioritizing work that will have the biggest impact on the organization.

Stage 4. The DevEx team sets a charter and roadmap, and proactively identifies top needs across the organization. Eventually, the DevEx team will create a formal process for both identifying and prioritizing strategic work as well as for managing support in a way that does not interfere with the team’s strategic bets.

As for the latter, some teams do support rotations, others have a separate support team. Twitter, for example, has what they call a Tier 1 support team. Jasmine James, Twitter’s Senior Engineering Manager of Developer Experience, described how the Tier 1 support team works: ‘In our engineering effectiveness group, teams that actually owned services were being weighed down by constantly engaging with customers to solve problems. We needed a centralized way to free up bandwidth for the strategic work, so we created a global Tier 1 support team, which is a place where developers can go and ask for help and either get pointed to existing documentation or get help triaging a ticket in the right team’s queue.’

Beyond establishing a formal support process, some DevEx teams also hire product managers (PMs) to help their team be more proactive. A dedicated PM can help the team do a better job of listening to customers, defining personas, prioritizing work, and getting adoption.

How developer experience teams prioritize strategic work

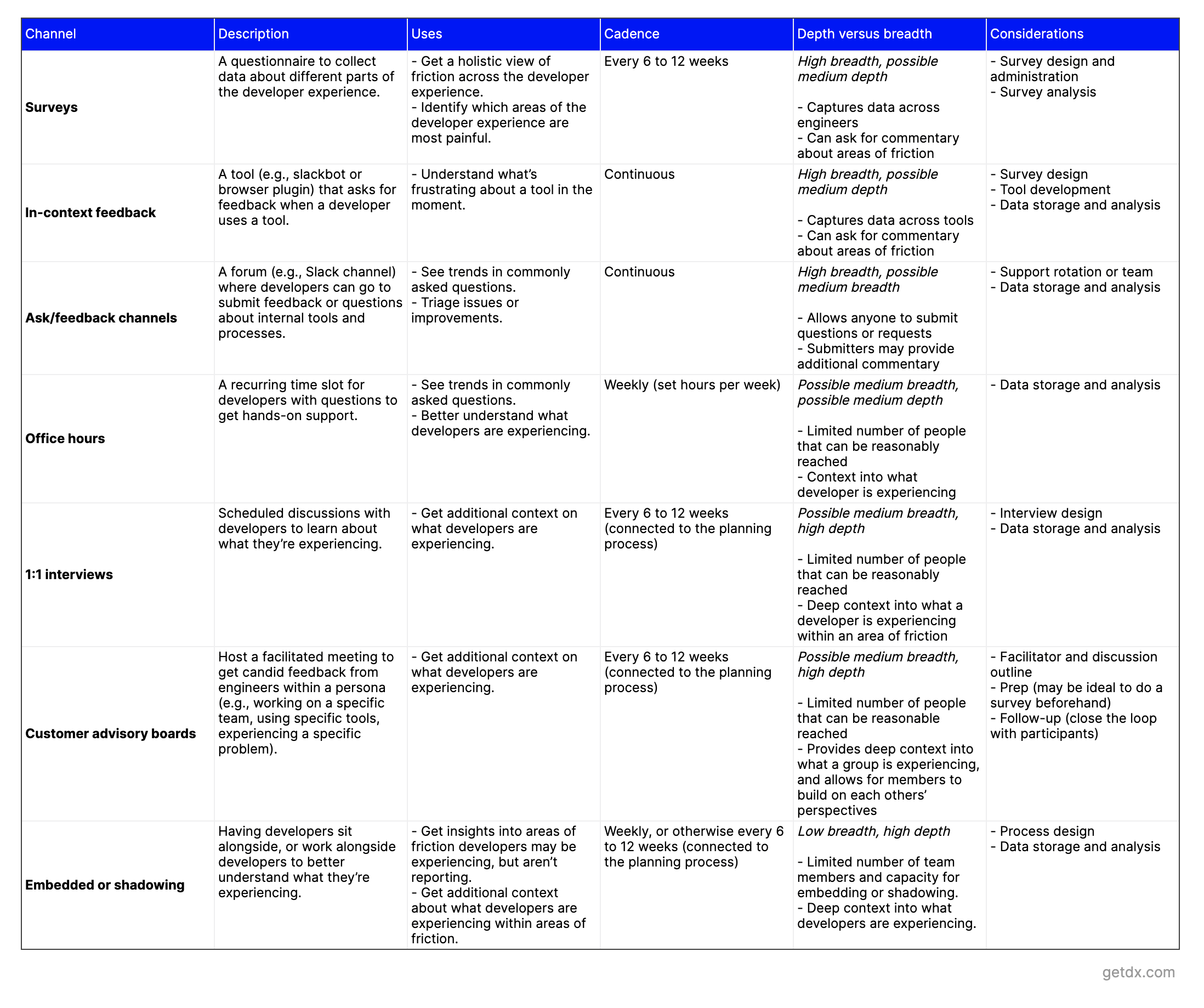

DevEx teams work with engineers to learn which problems are a priority. Just as an external-facing product team gets customer feedback, developer experience groups also use an array of channels for listening to developers.

Here are some of the channels we’ve seen DevEx teams use:

Through these channels, the DevEx team can gather data about where developers are experiencing friction, what exactly they’re experiencing and when, and how painful different areas of friction are.

When prioritizing what to focus on, teams may take these points into consideration:

1. Is the issue isolated to a specific team or systemic across the organization? DevEx teams can think about their scope as being split into two categories: things they can change first and then influence, and things they can only influence.

- Things they can change: issues experienced across teams. Think tools, tests, builds, environments, or documentation. DevEx teams can directly change these areas but will need to focus on getting adoption of the tool or process.

- Things they can only influence: any issues that are isolated to specific teams. DevEx teams may provide best practices or guidance for team leads to drive their own improvements.

2. Which developer persona do we need to serve? If there are engineering teams focused on mission-critical projects, it may be worth prioritizing the issues experienced by those groups first. (To learn how Twitter considers personas as part of their DevEx prioritization, check out this interview.)

3. What level of ongoing work will this problem require moving forward? An introduction of a new tool will likely require support and maintenance. If the investment is in a process, like documentation, a team may consider whether they need to continue coaching teams on how to write or find documentation moving forward. Or technical debt: is the problem specific to an area of the codebase and fixable within a time period, or should the DevEx team instead focus on preventing high interest tech debt longer-term?

4. What is the cost of this problem? We’ve seen teams take different approaches to calculating the cost:

- Expected gain to the company. What is the context-switch time on top of the wait time (or wasted time) for this task? If we take that number with how frequently a developer moves through that workflow, we can calculate the expected boost in productivity from making the workflow more seamless.

- Cost of time wasted. Take the average engineer‘s salary, multiplied by ~1.5 to 2X, to calculate their cost per minute or hour. (This is called the ‘fully loaded cost’ of an engineer, and accounts for the non-salary overhead that is spent on engineers, like their laptop, software licenses, amortized benefits, facilities costs, etc.) Multiply the engineering cost by the amount of time spent waiting, redoing work, or context switching within a part of the development process.

- Cost of a delayed investment. Determine the cost of delaying an investment in resolving the problem for a period of time. If the problem is costing the organization an average of $400,000 per week, we can calculate the cost of not investing in the problem for three more months, six months, a year, and so on. (Note: this argument may resonate more with non-engineering groups like product, helping developer experience leaders more easily justify investments.)

These approaches each provide a different perspective on whether, when, and how a developer experience group may take action.

How developer experience teams get adoption for tools or processes

If a team has done the work to understand their customers’ problems, there is a fairly standardized framework for getting adoption for the tool or process change:

Before releasing for general availability:

- Identify early adopters. These may be the same people who vocalized the problem through surveys or slack channels or otherwise have volunteered to test and provide feedback.

- Release a prototype to early adopters. Get early feedback from the group of volunteers, and identify edge cases. For example, in their effort to move to remote development environments, Slack’s developer productivity group released a minimal remote development workflow to beta users, then spent a couple of months addressing limitations reported by those users. Then they released for general availability.

- After releasing to the general audience, get feedback on the change from users.

Interesting tactics for getting adoption:

Sometimes, a new system will catch on and spread through an organization from word of mouth. Even still, it can help expedite the process if the developer experience team focuses on spreading the word.

Internal DevEx teams may apply some of the tactics that external DevEx teams use to get adoption:

- All hands meetings, or show-and-tell meetings. Share the story of why the tool or process was implemented and the results users are seeing.

- Events. Host events, like hack days, centered around helping users learn about and adopt the change.

- Community. Create a place where people can learn about your team’s work and talk with other users. The format can vary: a newsletter that allows discussion, a slack channel, or an internal podcast.

- Embedding. Have a DevEx team member join a team for a sprint or two to help them adopt the change.

- Showcase team/internal champion. Have a development team that’s using the process/tool share their case study about the benefits they’ve had and are continuing to get.

- Building the golden path. Build the tools/script into automated processes for common tasks. This might include ‘bootstrap’ configuration for new microservices, or dropping a plugin/module into a build tool that makes it easier for people to adopt tools.

If the change isn’t catching on, it’s possible that the team missed something in their research with regards to the pain points developers experience or the existing ways they’re already mitigating them. It’s a high cost to solve a problem in the wrong way. That’s why it’s critical that teams spend time understanding issues before diving in.

2025 developer experience salaries

As a DevEx engineer, salary ranges vary depending on location, but in some areas, you can expect to be well-compensated for your efforts. Pulling from some publicly available sources, here’s what you can expect in terms of pay in 2025:

- According to Glassdoor, in the United States, the average compensation for an engineering manager is around $155,000, with around $121,000 of that being base salary and the rest additional pay in the form of bonuses, stock grants, and so on. That average is part of a typical range that can go from $94,000 on the lower end to $154,000 on the high end.

- In the United Kingdom, compensation is lower, according to Glassdoor: the median pay is around £35,000, in a band that ranges from £25,000 to £42,000.

- If you’re looking for engineering manager work down under, the average pay in Australia in this role is A$65,000, according to Talent.com. That can go up to A$172,000.

Parting words

More companies are investing in developer experience teams as a way to improve productivity by reducing friction, delays, and areas of frustration for developers. As such, we’ll need to work to get clear on what these teams do and how they work at different company stages. I hope this article has been a step in that direction.

Thank you to Michael Galloway, Laura Tacho, Jasmine James, Julio Santana, Pat Kua, and Willie Yao for providing input and feedback on this article.