Performance management comprises many different parts that can be difficult to track. Learn about strategies and practices you can implement to help make shaping your teams easier.

Photo by David Trinks on Unsplash

Since the early 20th century, management has evolved from hierarchy-based, top-down rigid structures, to new agile-minded contexts where the employee is empowered, and teams have more autonomy to set the right performance goals that align with the company strategies.

In 2010, Jurgen Appelo created the Management 3.0 model to gather principles and practices aligned to this new era, which demands that companies be more adaptive and less top-down. In the face of this complex shift, managers will have to create impact while empowering teams and people to reach their best performance.

What do we mean by performance?

There are a lot of definitions of performance out there, but the below definition is a good guiding tool:

Employee performance is how employees fulfill their duties and execute their required tasks. It refers to the effectiveness, quality, and efficiency of their output. – WalkMe Team

To complete this definition, I would add that employee performance also refers to their outcome and behavior.

- Behavior: This is key in performance. The behavior of a single member of a team influences its health and climate, impacting efficiency, trust, and cohesion with other members. It is about their interpersonal skills and their daily attitude. Behavioral goals are more difficult to measure than output or outcome, but their impact is more significant in the long term.

- Outcome: People with an outcome-driven mindset have a clear understanding of what problems need to be solved and they know how to find solutions to solve them. This is someone who goes above and beyond, instead of just executing tasks given to them by a manager. Outcome measurement is probably more difficult than counting delivered tasks, but it will ensure we work in the right direction.

Performance: Common misconceptions to avoid

No company is the same; employees and managers can understand performance differently.

The following list of things should not be understood as performance, but sometimes they are.

“Hard work”

In some companies, hard work can be understood as work outside of working hours, even on weekends. This behavior can also be praised, even in public.

Some employees think sacrificing their free time is necessary if they want to be perceived as top performers. But prolonged hard work burns out people and generates stress that impacts them physically and psychologically.

Instead of praising this toxic, hard work, we should analyze what processes require extra effort and find healthier and maintainable working methods.

An objective metric

We can count on several commercial platforms and tools that provide engineering output metrics from different sources like Github, Jira, etc. We can also create ad-hoc tools to gather metrics about other team performance aspects.

Having metrics is essential, but they will tell us only a part of the story.

Despite our efforts to make the process objective and fair, performance evaluations and metrics are mostly subjective. We should maintain frequent conversations and gather feedback continuously to ensure the overall picture of a person’s performance.

Avoid relying only on automated tools as this will result in a poor performance management experience for an employee.

Engagement

Employee engagement is the emotional commitment and belonging they have to their company. This commitment is based on intrinsic motivation beyond salary, promotions, and other rewards.

Low levels of engagement are a clear indicator that management, not the engineers, needs to take action to address the intrinsic problems that influence it.

Low participation in the company engagement surveys can be also an indicator of the same thing. Asking people to participate in an engagement survey as if it were a performance goal will drive them to complete the survey instead of delivering honest feedback about their motivations.

Performance management practices

Ensuring continuous conversations

Performance management requires continuous conversations at different levels. The below is a great definition of performance management:

Performance management is an ongoing dialogue between you and your employees that links expectations, data gathering, ongoing feedback, development planning, performance appraisals, and follow-up. – University of Texas

So even if we have an annual or quarterly performance review, make sure conversations around performance happen continuously in the team and in 1:1 meetings.

At the team level

Conversations at the team level are imperative. We should enable spaces to ensure alignment through values and principles, review impacts and expectations of the work done, and follow up on the team’s climate.

If we have team metrics, we can share insights and have weekly conversations around them. Team metrics are owned by the entire team and not only by the managers. The team can also challenge the metrics they have and propose new ideas around them.

At a personal level

1:1 meetings are an excellent opportunity to discuss performance continuously. Ideally, there should be space to discuss goals and impacts, in addition to giving and receiving feedback bi-directionally between the manager and the employee.

Setting goals

As managers, we should guide employees so they can appropriately define their career goals, making sure their objectives and aspirations balance their growth and the company strategy equally.

The goals must be realistic and achievable. In this sense, less is more. A good practice is having a small set of goals following the SMART principle: specific, measurable, assignable, realistic, and time-related.

If some goals are difficult to measure, we should rethink the scope or the specificity. For example, instead of writing a goal like “become a reference at a technical level”, we can be more specific with “become a reference at a technical level by sharing lessons learned using technology X in production.”

We must also be specific about the outcome, avoiding goals like “give five talks internally or in a community conference”. This is an output-based goal, that doesn’t really measure outcome. For instance, impact varies significantly between a presentation given to summarize product documentation vs. one that shares real experiences with valuable lessons.

Assessing performance

Companies use different approaches to assess people’s performance homogeneously. Normally they use a scale like: top performer > above expectations > on expectations > low performance.

Managers can use these scales to assess a general result or different results they need to evaluate, such as communication, delivery, team player, or leadership.

Keeping the process simple will enable more productive conversations about performance between the managers and their reports; adding more layers to the assessment process will make it more complex to be understood by everyone in the same way

Performance reviews

Performance reviews act like checkpoints for companies to evaluate their employees’ performance. They can happen once a year, or once every quarter.

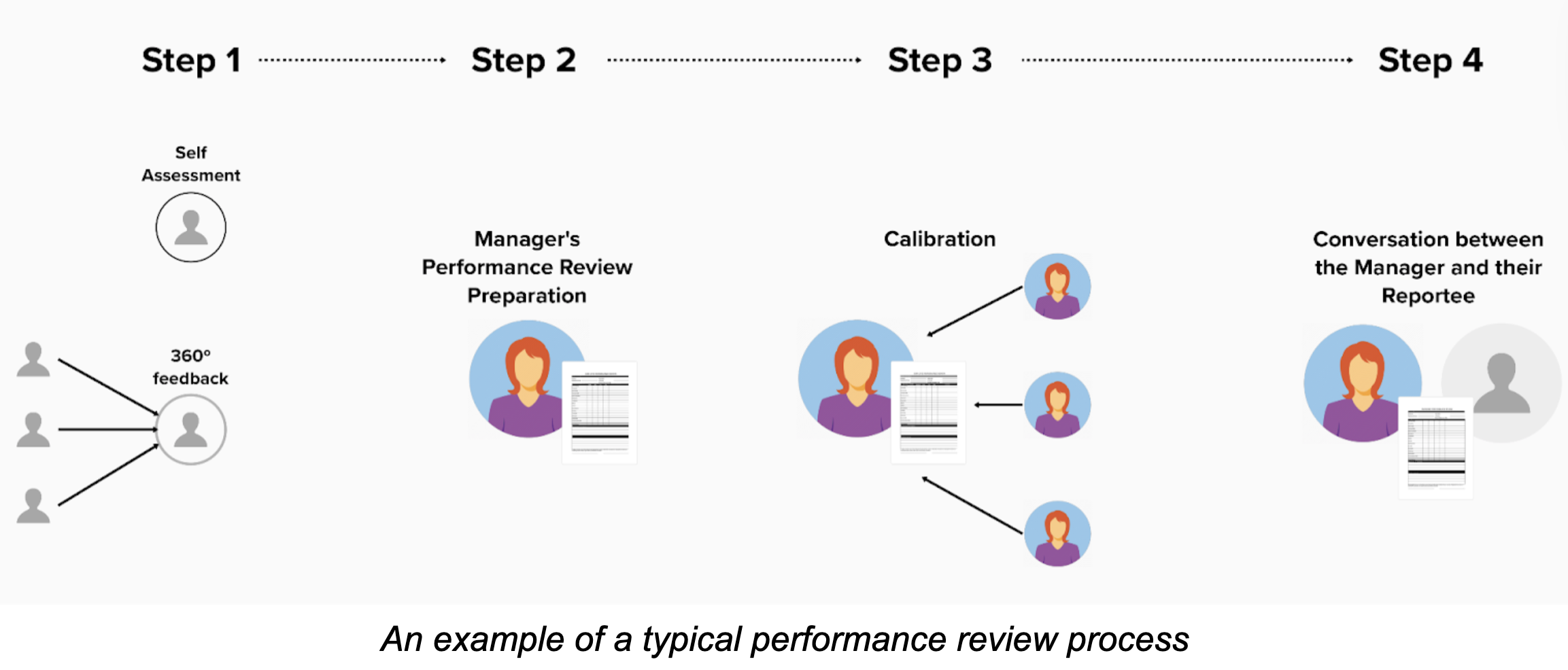

With a typical performance review, the process starts by asking people to do a self-assessment as a retrospective since the last performance review.

During this stage, it is not uncommon for colleagues to be asked to give feedback on a teammate’s performance via a 360 feedback survey. This practice is beneficial to gain a broader overview of an employee’s performance as managers now have a diverse pool of opinions to pull from.

Using these, managers prepare the assessment and performance review. It will be written down in a document shared with the person.

They schedule a meeting with each report in advance to review the different aspects of their performance, goals, and assessment results. The managers should be able to deliver feedback that guides the next goals after the review.

Calibration

Some companies implement a calibration exercise before managers converse with their reports. In this exercise, each manager presents the performance of their reports’ assessment results to other managers, directors, and people in the leadership team.

The benefits of the calibration are the following:

- Avoiding over and under-calibration: this exercise ensures that a report’s general evaluation is consistent cross-teams, avoiding bias in the evaluations. This also mitigates disproportionate results where a high percentage of people are classed as top performers or under-performers. In those situations, we need to discuss our expectations and measurement criteria.

- Ensure homogeneous performance assessment criteria: every manager can deliver feedback about how others are evaluating people’s performance. Different points of view can be beneficial to align the management team and avoid personal bias that can translate into unfair situations for the engineers.

- Getting broader context about the people’s performance: for other senior roles, it is beneficial to count on a high-level overview of people’s performance outside of their own teams.

Not all companies have an official calibration process, but it is an interesting practice that we can do in the engineering management team. When they are part of the official performance review process, they’re usually led by the HR department to ensure that all the departments in the company follow the same principles.

Performance reviews are known for being time-consuming

Despite there being platforms that automate part of the job, doing the performance review process right still requires a significant amount of time from the managers and engineers, but we can do some things to reduce the load that this exercise demands.

Information gathering can often be the most taxing stage for many people involved in the process. For example, 360-degree feedback requests can overwhelm engineers who are asked to provide input on many people. As managers, we should distribute our requests correctly and avoid always asking the same people to give feedback to each of our direct reports.

Another way to help in this regard is to avoid postponing general information gathering at every stage, making sure performance assessment is a continuous practice.

Managing low performance

Low performance can be reflected in a decline in a report’s outcome, delivery, or behavior.

Low performance is a rare occurrence. When these cases arise, managers need to know what variables can be changed to improve them. Sometimes, solutions like moving that person to another team are effective in improving their performance. Unfortunately, the solution is not always that simple.

Managers are facing complex situations frequently. Some typical examples include problems at home, anxiety, psychological problems, or lack of feedback from their previous managers or workmates.

Mutual trust between the manager and employee makes things easier for helping an employee whose performance may have dropped. It is crucial for managers to ensure their reports trust that they get visibility about what is going on at the company. Trust also comes from a manager’s team knowing they have someone to turn to in challenging situations.

Continuous conversations and feedback ensure trust between managers and their direct reports. And they are essential when low-performance issues arise.

Constant discourse is also important for avoiding surprises. This mitigates situations where assumptions are made about if a report already knows their opportunities and expectations while allowing room for feedback to be understood by the team member.

When repeated feedback doesn’t work, we should have a clear, time-limited plan to tackle the performance issues. If we wait too long, one person’s performance can affect other team members, impacting morale and overall productivity in the worst case.

Improvement plans

If the manager thinks their report can improve their performance in a limited period after their conversations and feedback, they can design a performance improvement plan (PIP).

This plan is recommended to include short-term goals with a clear, short-term end date. It would be a good idea to count on our HR workmates’ presence when we show the PIP to the person.

Some companies use PIPs to “check the box” before letting people go, a bad practice that hides the value of this tool.

Instead, we can see how GitLab understands the PIP plan:

“At GitLab, we think that giving someone a plan while you intend to let them go is a bad experience for the team member, their manager, and the rest of the team.

A PIP at GitLab is not used to “check the box” a PIP is a genuine opportunity to help clarify underperformance and areas of focus. You should only offer a PIP if you are confident that the team member can successfully complete it.”

A PIP is a tool that can be useful when the person has the attitude to improve their performance or when the performance improvement is achievable in a reasonable period, for example, two or three months. When this is not possible, we must let the person go.

In other exceptional cases, the person’s attitude and behavior are against the team’s fundamental values and principles. Here, PIPs will be ineffective and if we don’t act fast with this person, the team’s morale and climate will be impacted negatively.

Managing top performance

Outstanding performance is something that, as managers, should make us happy and proud. These situations are as unique as the low-performance ones. As such, there are some considerations to take into account:

Recognize

Recognition can be an effective way to positively impact people’s motivation. It is also important to consider that public recognition can make some people uncomfortable or stressed.

Managers should know how to praise and recognize their people. In certain cases, they can look for alternative communication channels where the person feels comfortable without causing unnecessary anxiety.

Top performance should be exceptional

“Top” or outstanding performance means that the person has achieved something remarkable beyond our expectations for their level or role.

Managers assessing many people as “top” performers should trigger alarm bells. Although some exceptional situations could happen, managers should ensure this result is held only for people who achieved outstanding performance to avoid losing credibility.

Additionally, if managers have a trend of over-evaluating employees’ performance in a team it can be perceived as unfair to other engineers in other teams who had similar performance but didn’t get the same results.

Top performance is not equal to a promotion

Being considered a top performer in a performance review doesn’t mean the engineer is ready to assume a more senior role they are pursuing.

For example, a senior engineer in pursuit of a management role who has consistently shown outstanding performance may need to have a period of time before promotion to hone their skills in preparation for assuming responsibilities. This will help them avoid frustration, burnout, or other personal impacts in the long run.

Sometimes the person can’t be promoted because of limits that are not in the person’s or manager’s control. For example, with some senior roles, the boundaries of the company structure limit the number of people hired or promoted at a certain time.

Some personal lessons I learned

People should own their performance and growth

Managers are accountable for evaluating and guiding people to achieve their best performance and growth. But in the end, the person should be the owner of their performance. They should decide their goals and take advantage of all the opportunities to achieve them.

Of course, the manager should help them and give guidance if needed, but they can’t decide on personal goals for them.

Managers are not psychologists

It’s dangerous for a manager to see themselves as a psychologist.

Though a manager’s best intentions may be at play here, it is very credible to cause more hurt than good when trying to help people without being a professional psychologist.

Even if a manager has received training in some specific aspects, psychology is a science and a different profession. A more qualified professional should be the one who is turned to in aspects beyond the engineering manager’s scope.

We should tackle low performance, fast

It is a common mistake to wait too long before facing a bad performance problem.

When a person doesn’t meet expectations or their behavior is not acceptable, other team members will be impacted. Health aspects like climate and cohesion will be negatively affected and people will lose trust in the person whose performance is low, and teams can lose faith in the support offered by management.

Values and principles over precise definitions

Guidelines and clear process definitions are helpful to ensure that people know what is expected from them, in both their day-to-day tasks and their overall roles.

The problem is that the expectations can evolve and change. If these guidelines are too detailed in trying to cover all possible expectations in detail, people can perceive them as static contracts that they have to follow “to the T”. This can stop them from thinking for themselves or adapting in order to find better solutions, alongside struggling to cover gaps that are not defined.

Instead, if we ensure the understanding of our values and principles, they can guide conversations in the teams about how to act when a situation occurs, or when managers are not present in the teams. Once they understand the principles behind the expectations, it will be easier for them to challenge and adapt them when the context changes.

Caution with rewards

In 1993 Alfie Kohn (author of Punished by Rewards) published his famous article Why incentive plans cannot work. It describes how incentives only guarantee temporary compliance; they are ineffective long-term and can even negatively impact people’s performance. For example, when they are not offered anymore, you may see a dip in their performance.

If we don’t work properly in generating true engagement with the company, people will find a way to hack the system to get rewarded instead of truly looking to improve their performance.

“Good hiring” is fundamental for performance

Performance is contextual. The expectations regarding good performance can vary between companies i.e., low performers in one company can be great in others and vice versa. The first step to reducing low-performance situations is ensuring cultural-fit validation in hiring processes.

As managers, we should ensure that hired people are aligned with our values and principles, to ensure higher levels of performance.

Final thoughts

Understanding what we mean by performance is the most important step before managing it. In this article, we have reviewed some understandings about it and how to approach its management process.

Despite the tools and processes implemented in our companies, continuous assessment and conversations around performance between managers and engineers are essential to provide feedback and guidance. This guidance will benefit goal setting, fix low-performance issues, and reach top-performance levels.

Managers will help, but in the end, the engineers should always be the owners of their performance.